Teeth show ancient divide

A high-tech study of teeth has exposed ancient gender inequality in China.

A high-tech study of teeth has exposed ancient gender inequality in China.

The research casts light on breastfeeding, weaning, evolving diets and the difference between what girls and boys were eating.

The teeth come from the Central Plains of China sometime in the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, between 771 and 221 BC. This makes them about as old as Athens’ Parthenon and the Old Testament sacking of Jerusalem’s First Temple.

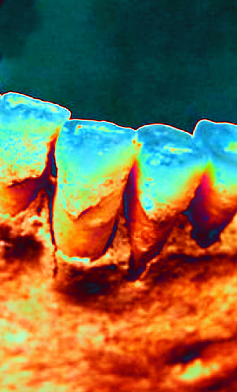

Even so, the teeth’s dentin – the bony tissue forming the bulk of human tooth structure – was full of information when subjected to isotope analysis.

“We already knew this [Eastern Zhou Dynasty] time period showed increasing inequality between men and women,” lead researcher Dr Melanie Miller.

“What we were able to find is that these differences were even evident in what people ate and how they cared for their children, such as gender differences in how long babies were weaned and then the foods they were fed as children.”

The analysis of 23 individuals from two different archaeological sites shows children were breastfed until they were between 2.5 and 4 years old, with weaning onto solids – consisting mostly of wheat and soybean – occurring slightly earlier in females than in males.

“Food was an integral aspect of identity, and it was a medium of differentiation between females and males,” Dr Miller said.

“We found dietary differences between the sexes began in early childhood and continued over the lifetime.”

Males continued to eat more of the traditional crop, millet, while females consumed more of the ‘new’ foods such as wheat and soy, Dr Miller says.

The Eastern Zhou Dynasty is a very important period of Chinese history and Chinese cultural change; it is the time of Confucius and other notable intellectuals, Dr Miller says.

“And we are seeing some of the earliest forms of social inequality between men and women emerge during this time, and these dietary results underscore how the daily lives of women and men were increasingly differentiated, even in daily practices such as what foods a person ate,” she said.

Dr Miller says the chemical techniques used in this type of bioarchaeology are making it possible to study ancient human dietary practices over those peoples’ lifetimes.

“With this approach we’re getting personalised glimpses into the lives of ancient people. That can reveal significant aspects of their life experiences, including things like gender divisions and social inequality.”

Print

Print