Studies line kids up for disappearing jobs

A new study says that 60 per cent of Australian students are studying for jobs that will not exists, or be very different, in 15 years’ time.

A new study says that 60 per cent of Australian students are studying for jobs that will not exists, or be very different, in 15 years’ time.

The report - New Work Order: Ensuring Young Australians Have Skills And Experience For The Jobs Of The Future, Not The Past – says students in vocational education and training (VET) will be hit the hardest by big developments set to change the way we work.

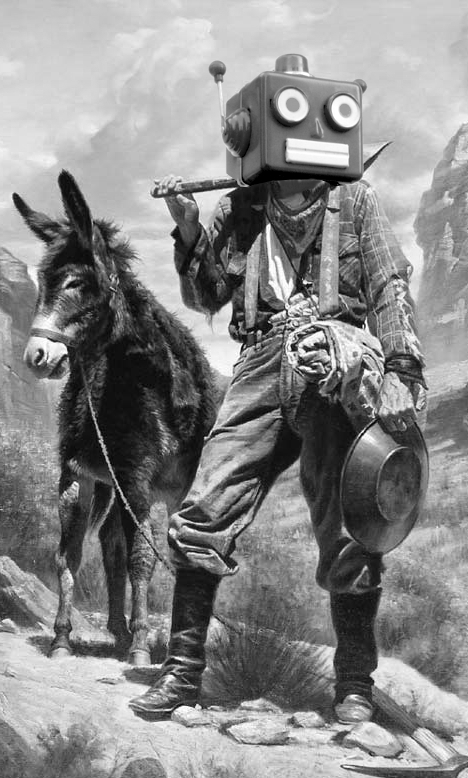

Automation in the form of robots and other mechanical devices are the biggest threat, followed by the risk of redundancy due to advances made by ‘in-the-box’ technology, like advanced algorithms and forms of computer control.

The Foundation for Young Australians’ (FYA) CEO Jan Owen has told reporters that a big educational overhaul is needed.

“Australia is already facing the challenge of an ageing population and the subsequent shrinking workforce and if our nation is going to overcome these challenges, young people must be given the opportunity to drive the economy forward,” she said.

“The future of work is going to be very different. Many of the changes could be great for our nation, but they could also be devastating – for young people in particular – if we don’t take the right actions to prepare for this vastly different world.

“Today’s 12-year-old won’t have the same opportunities to get a start in the workforce.

“Technology and globalisation are making it easier and cheaper for people to start their own business; and new technologies and ways of working are making how and where people work more flexible. If we are to make this work in our favour, we need to position our young people for success.

“Our report found more than 90 per cent of Australia’s current workforce will need digital skills to communicate and find information in order to perform their roles in the next 2-5 years. At least 50 per cent will need advanced skills to configure and build systems.

“To manage this demand and ensure Australia’s young people can thrive in this environment, the next generation need to not only know how to operate technology, but how to create and manipulate it as well. Our children may be able to operate a smart-phone with ease, but what they need is to learn how to build it.

“Unfortunately, our national curriculum is stuck in the past – with the current recommendation that teaching in digital skills not commence until Year 9. This is despite the international evidence that says we must go early.”

Analysts at PriceWaterhouseCooper recently prepared the following table, based on a similar report.

Print

Print