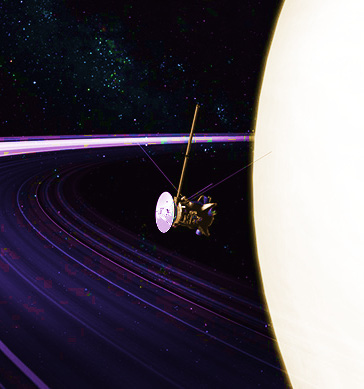

Cassini farewelled on final descent

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft will soon finish its 20-year mission to explore Saturn with a dramatic dive into the planet.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft will soon finish its 20-year mission to explore Saturn with a dramatic dive into the planet.

After spending 147 days spiralling between Saturn’s rings and the planet, with 22 dives into the mysterious and uncharted territory, the craft will enter Saturn’s atmosphere on Friday night.

As it plummets to its fiery doom, its will beam back data in real time to the CSIRO team at the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex.

NASA has already extended the mission in the past, but now operating scientists are worried that with propellant running low, the probe might otherwise have accidentally crashed into one of Saturn's nearby moons, potentially contaminating it with Earth bacteria stuck to the spacecraft.

Any biological matter is expected to burn up in Saturn’s thick atmosphere.

Cassini has been a scientific workhorse for over a decade, providing fascinating insights into the Saturnian system since arriving in orbit in 2004.

Cassini has sent back unprecedented information about the structure and dynamics of Saturn’s atmosphere, its moons and its rings, teaching scientists about the atmosphere and surface of Titan and its lakes of methane, and about the subsurface liquid ocean of Enceladus and its jets that erupt from its surface.

Enceladus was once thought a giant ice ball, but observations of its poles have revealed geysers spewing water far out into space that suggests a liquid water ocean may be present beneath the surface.

It is even possible that this ocean could host life that resembles primordial life deep in the oceans of a young Earth. Scientists say it is imperative that another probe be sent to Enceladus in the near future to find out more.

There have been some bizarre findings about the moon Hyperion, which has a very low density and resembles a giant sponge, as debris impacts penetrate deep into its surface.

Besides its strange appearance, Hyperion has a statically charged surface, they only other one ever observed besides our own moon.

Some of the most interesting findings of the overall mission were from the Huygens lander (a craft designed by the European Space Agency) that Cassini carried, which landed on the moon Titan in 2005 - thereby becoming the most distant landing ever.

Huygens revealed a moon with an atmosphere 50 per cent thicker than Earth's atmosphere, above a landscape sculpted by methane rain, methane rivers and methane lakes - a methanological cycle at -180°C, comparable to the hydrological cycle at +15°C of our home planet.

Cassini is named after a 17th-century astronomer famous for discovering four moons of Saturn and discerning the structure of Saturn's rings.

The Cassini probe inspected both the moons and the rings at a level of detail that could not have been imagined by Cassini himself.

The probe has shown that the rings are incredibly thin, less than a kilometre thick, and shepherded by a number of small moons. They are a mixture of mud and ice.

In passing inside the rings, Cassini can determine the gravitational perturbation associated with the mass of the rings. The higher the mass in the rings, the older the rings are likely to be.

The shepherding moons are pushing and pulling the material in the rings, causing friction and likely evaporation. The rings must be relatively young, but that still means they could be hundreds of millions of years old.

Even in its final hours, Cassini may help resolve one of the greatest mysteries of Saturn - what lies beneath its shrouded veil.

Print

Print