Multi-cell emergence pushed back

New findings roll back the date for when multicellular life emerged on Earth.

New findings roll back the date for when multicellular life emerged on Earth.

Scientists at the Swedish Museum of Natural History have found 1.6 billion-year-old fossils resembling red algae in uniquely well-preserved sedimentary rocks at Chitrakoot in central India.

One type is thread-like, the other one consists of fleshy colonies.

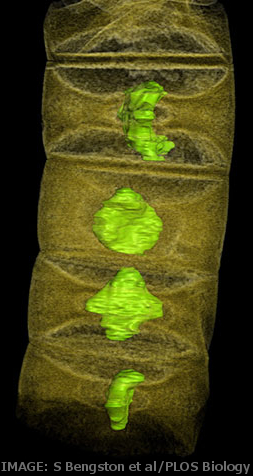

The scientists were able to see distinct inner cell structures and so-called ‘cell fountains’, the bundles of packed and splaying filaments that form the body of the fleshy forms and are characteristic of red algae.

“You cannot be a hundred per cent sure about material this ancient, as there is no DNA remaining, but the characters agree quite well with the morphology and structure of red algae,” says Professor Stefan Bengtson.

The earliest traces of life on Earth are 3.5 billion-year-old single-celled organisms, while large multicellular eukaryotic organisms did not become common until about 600 million years ago, near the transition to the Phanerozoic Era, the ‘time of visible life’.

The oldest known red algae before now were 1.2 billion years old, but the Indian fossils are 400 million years older, and would be by far the oldest plant-like fossils ever found.

The research group was able to look inside the algae with the help of synchrotron-based X-ray tomographic microscopy, which allowed them to see regularly recurring platelets in each cell, which they believe are parts of chloroplasts - the organelles within plant cells where photosynthesis takes place.

They have also seen distinct and regular structures at the centre of each cell wall, typical of red algae.

The experts say this suggests that the early branches of the tree of life need to be recalibrated.

“The ‘time of visible life’ seems to have begun much earlier than we thought,” says Stefan Bengtson.

The presumed red algae lie embedded in fossil mats of cyanobacteria, called stromatolites, in 1.6 billion-year-old Indian phosphorite.

The thread-like forms were discovered first, and when the then doctoral student Therese Sallstedt investigated the stromatolites she found the more complex, fleshy structures.

“I got so excited I had to walk three times around the building before I went to my supervisor to tell him what I had seen,” she says.

Print

Print