Huge new sea scorpion surfaces

Evidence of a previously unknown ancient sea monster has been uncovered in the USA.

Evidence of a previously unknown ancient sea monster has been uncovered in the USA.

The fossil of a giant ‘sea scorpion’ measuring over 1.5 metres long was found in Iowa.

Dating back 460 million years, it is the oldest known species of eurypterid (sea scorpion) - extinct predators that swam in ancient seas and are related to modern arachnids.

The authors named the new species Pentecopterus decorahensis after the 'penteconter' - an ancient Greek warship that the species resembles in outline and parallels in its predatory behaviour.

“The new species is incredibly bizarre,” says lead author James Lamsdell from Yale University.

“The shape of the paddle - the leg which it would use to swim - is unique, as is the shape of the head. It's also big - over a metre and a half long.”

“Perhaps most surprising is the fantastic way it is preserved - the exoskeleton is compressed on the rock but can be peeled off and studied under a microscope.

“This shows an amazing amount of detail, such as the patterns of small hairs on the legs. At times it seems like you are studying the shed skin of a modern animal - an incredibly exciting opportunity for any palaeontologist.”

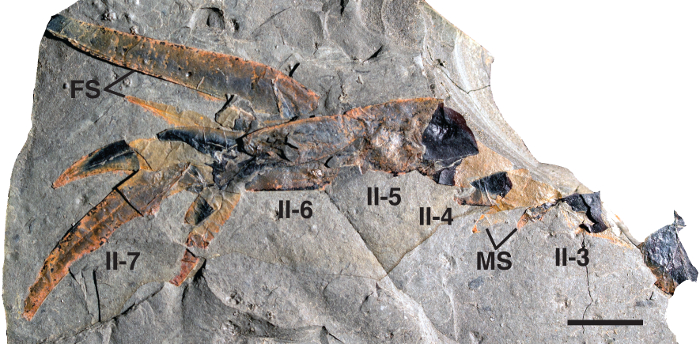

The new eurypterid species is represented by more than 150 fossil fragments, excavated from the upper layer of the Winneshiek Shale in northeastern Iowa - a 27 metre thick sandy shale located within an ancient meteorite impact crater and mostly submerged by the Upper Iowa River.

Some large body segments suggest a total length of up to 1.7 metres, making Pentecopterus the largest known eurypterid from its era.

Pentecopterus is about 460 million years old - ten million years older than the previous oldest record of the eurypterid group.

Some features of Pentecopterus revealed in the fossils also allow the researchers to interpret the functions of certain body parts.

Some features of Pentecopterus revealed in the fossils also allow the researchers to interpret the functions of certain body parts.

The rearmost limbs include a paddle with a large surface area, and joints that appear to be locked in place to reduce flex. This suggests that Pentecopterus used these paddles to either swim or dig.

The second and third pairs of limbs may have been angled forward, suggesting that they were involved primarily in prey capture rather than locomotion. The three rearmost pairs of limbs are shorter than the front pairs, suggesting that Pentecopterus may have walked on six legs rather than eight.

The exceptional preservation of the exoskeleton also helped the researchers to interpret the role of finer structures, including scales, follicles and setae (stiff bristles).

The rearmost limbs are covered in dense setae. These form arrangements similar to swimming crabs, where they function to expand the surface area of the paddle during swimming. But the smaller follicle size in eurypterids suggests that the setae could have had a sensory function.

Spines are also present on some limbs and appear similar to those found on horseshoe crabs where they aid in processing food.

Print

Print