Clues sought for source of male rage

An Australian study is looking for the root of teenage aggression.

An Australian study is looking for the root of teenage aggression.

Researchers are recruiting for a study to reveal the drivers of aggression in boys, seeking new treatments to stem violent offenders in future generations.

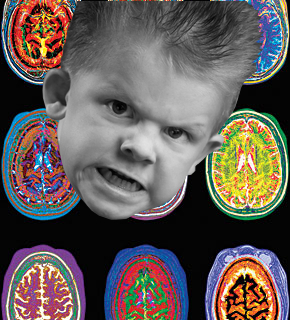

The latest in brain scanning technology will be used to explore distinct and different causes of aggressive and anti-social behaviour, each with different neurological pathways, in boys aged 8-16.

Psychological researcher Professor Mark Dadds says combative boys appear to fall into two groups – emotional-impulsive personalities who are overwhelmed and likely to lash out (they are referred to as ‘hyperstimulated’) and the more callous or ‘cold-blooded’ subtype.

“We think the majority of aggressive boys fall into the first group. They are living in a world where they’re interpreting us as being hostile to them,” says Professor Dadds, from UNSW Science.

“The issue for parents of aggressive kids who are emotional and impulsive is that they get drawn into a cycle of ineffective discipline such as shouting, hitting and getting in their face, which is just counterproductive.”

“But there is evidence of another group who simply are not registering you and I as having emotions, who operate in a world where everything is just an object.

“Instead of being oversensitive they are completely ignoring the signs of other people, and their violent behaviour can be more cold-blooded,” he said.

The study will use eye-tracking technology to see how brain activity differs between these two groups of violent youngsters. Investigations will focus on when a subject looks at people with varying facial expressions, and whether their brain activity changes.

Previous research has shown that callous children tend to not look at the eyes when shown images of emotional faces, which means they may miss vital emotional cues.

When explicitly instructed to look at the eyes, previous studies found the boys with more callous traits would correctly identify the emotion, indicating a potential area for early intervention with behavioural therapy.

A part of the brain called the amygdala, which processes external threats, is of particular interest.

Research suggests it is likely to be overactive in the emotional-impulsive boys, and underdeveloped in those with more callous behaviours.

Childhood aggression can be one of the first indicators of behavioural and psychological problems later in life.

Professor Dadds says children who tend to show different types of aggression will respond to different kinds of treatment, making proper diagnosis and management critical.

“If you think of those one-punch guys, many of them have been emotional-impulsive all their lives.” He said.

“They walk down the street thinking people are trying to fight them and seriously believe people are giving them looks.

“But there’s also a group in there who perceive someone’s knocked them and don’t even see them as human. They’ll just punch you to get you out of the way.”

The study is currently recruiting Sydney-based boys with aggressive behaviour between the ages of 8 and 16.

Print

Print