Anti-cancer mini-protein tested

Researchers are testing a drug to inhibit a gene that drives many cancers.

Researchers are testing a drug to inhibit a gene that drives many cancers.

Spanish researchers say a drug based on a mini-protein called OMO-103 shows promise in inhibiting the key cancer-causing gene, MYC, in early-stage human trials.

The customised protein is able to target a specific gene within tumours and block cancer growth.

It is the first time that such a treatment has been able to inhibit the function of the MYC gene in a phase I clinical trial. Until now, no other drug has been able to do this safely and effectively.

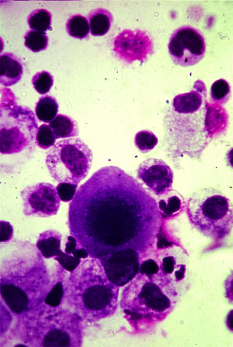

MYC is considered one of the ‘most wanted’ targets in cancer because it plays a key role in driving and maintaining many common human cancers, such as breast, prostate, lung and ovarian cancer.

To date, no drug that inhibits MYC has been approved for clinical use.

But scientists at the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO) in Barcelona have been working on the problem for several years, developing a mini-protein called OMO-103 that can enter cells and reach the nucleus.

In experiments in the lab and in mice, it has been shown to successfully inhibit the ability of MYC to promote tumour growth by blocking MYC’s function of controlling the flow of information from many common genetic mutations found in cancer.

A research team led by Dr Elena Garralda enrolled 22 patients to a phase I clinical trial to assess the safety of OMO-103 last year, and to see if there were any early signs of it controlling cancer.

The patients had a range of solid tumours, including pancreatic, bowel, and non-small cell lung cancers. They had all been heavily pre-treated, having received between three and 13 other treatments previously.

OMO-103 was given intravenously once a week at six dose levels, while the researchers took biopsies from the tumours at the start of the study and after three weeks of treatment to assess levels of MYC gene activity and other biological indicators for cancer.

Eight out of 12 patients who had CT scans after nine weeks were later shown to have stable disease, with the treatment having stopped the cancer growing.

“It’s still very early days to assess activity of the drug, but we are seeing stabilisation of disease in some patients,” Dr Garralda says.

“Remarkably, one patient with pancreatic cancer stayed on the study for over six months, his tumour shrank by eight per cent and there was a reduction in tumour-derived DNA circulating in the bloodstream. The patient with a salivary gland tumour has stable disease and is still in the study after 15 months.

“The most exciting thing is that biological markers show that we are targeting MYC successfully. In addition, the adverse side effects are mostly mild, which is important when we start to think about next steps and combining OMO-103 with chemotherapy or other therapies.”

She concluded: “OMO-103 is the first MYC inhibitor to successfully complete a phase I clinical trial and to be ready to proceed to a phase II trial. We have determined the recommended dose for phase II.”

The preliminary results from the trial were presented at the 34th EORTC-NCI-AACR Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics in Barcelona, Spain.

Print

Print